This guidance discusses the right to be informed in detail. Read it if you have detailed questions not answered in the Guide, or if you need a deeper understanding to help you decide what information to give individuals about your processing, and how to do this in practice. DPOs and those with specific data protection responsibilities in larger organisations are likely to find it useful.

If you haven’t yet read the ‘in brief’ page on the right to be informed in the Guide to Data Protection, you should read that first. It sets out the key points you need to know, along with practical checklists to help you comply.

-

What is the right to be informed and why is it important?

In detail

The transparency requirements of the GDPR create a number of overarching legal obligations for how you collect and use people’s personal data. The right to be informed encompasses some of the primary requirements in this area. It is about being open with people and providing them with clear and concise information about what you do with their data.

Articles 13 and 14 specify the types of information that you need to provide individuals with; we call this ‘privacy information’.

If you only obtain personal data as part of simple transactions, then it should be relatively straightforward for you to develop a clear and effective way to provide privacy information.

However, more complex uses of data can make it more difficult to convey all the required information, especially if you try to contain it in a single notice. The GDPR recognises this and allows you to use several different techniques to deliver the information.

Further reading - ICO guidanceFurther reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

Being open and upfront about what you do with their personal data helps you to deal with people in a clear and transparent way and empower them. This makes good sense for any organisation and is key to developing trust with individuals. Fostering trust in this way can help to improve the public’s confidence in public sector institutions, while private sector organisations can use it as a means of distinguishing themselves from their competitors.

Using personal data in ways that are invisible to people can create risks. It can leave people unaware of uses of their personal data that may lead to discrimination or disadvantage, and prevents them from exercising their rights. Being transparent helps to mitigate against these risks. Actively telling people about your use of their personal data will help them retain control over it and anticipate the potential consequences of its use.

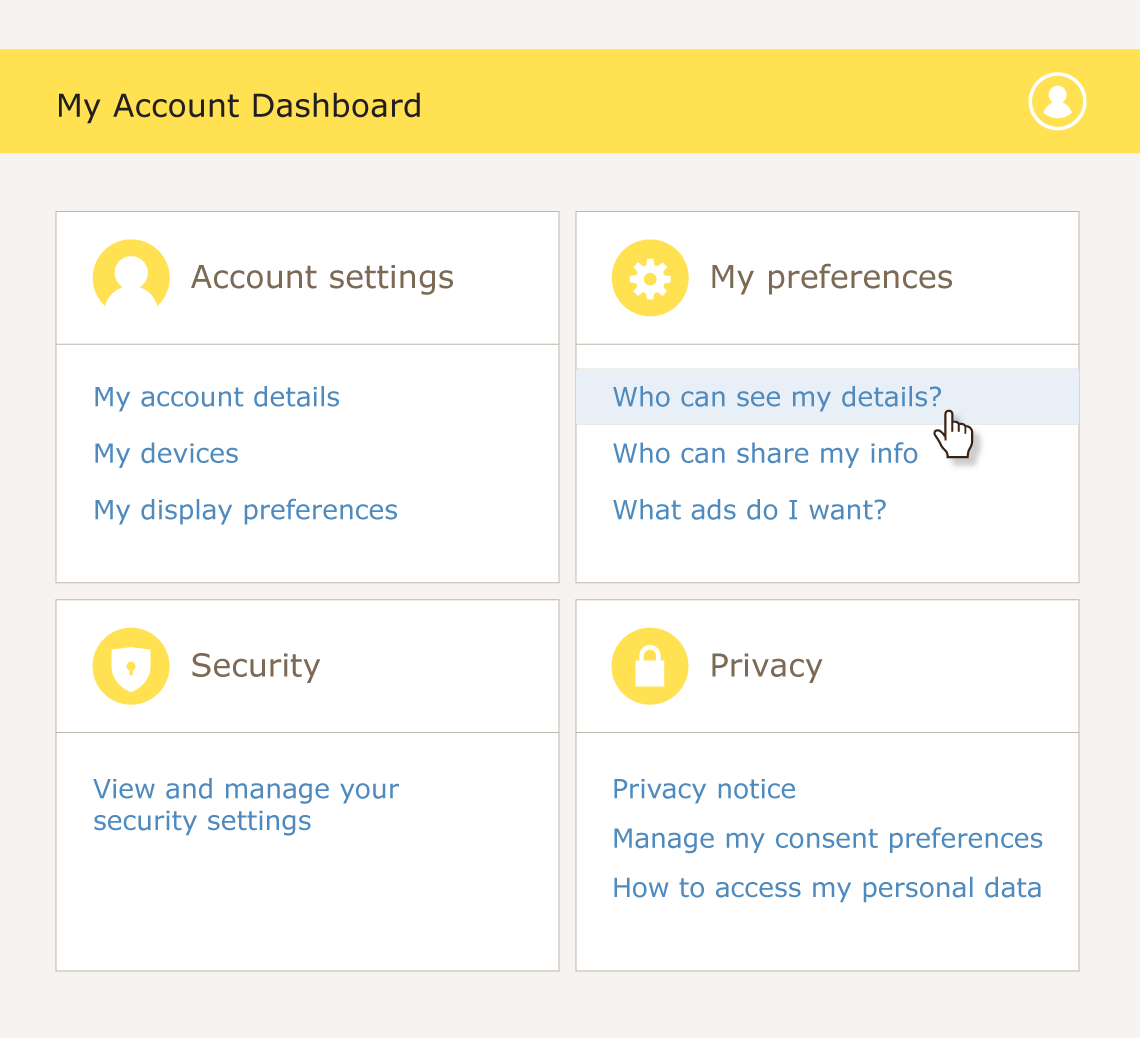

Combining the provision of privacy information with preference management tools, such as a dashboards (see "What methods can we use to provide privacy information?"), not only helps to empower individuals to understand what you do with their personal data, but also to exercise a degree of control over that processing. If individuals have more choice and are more engaged in what you do with personal data, you may be able to obtain more useful information from them. In turn, this can assist you to deliver better and more effective products and services. Providing privacy information also helps you with your broader compliance.

The right to be informed is not an end in itself and you should not treat it as a tick-box exercise just to achieve compliance with Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR. Providing individuals with privacy information in meaningful ways will also support compliance with a number of other provisions in the GDPR such as:

- Fairness – Fairness is about using personal data in a way that people would reasonably expect and considering what effects it may have on them. Drafting privacy information can encourage you to think more carefully about the impact and consequences of your processing. Making sure that what you tell people is clear and understandable will help to shape people’s expectations about what you do with their data.

- Purpose limitation – The principle of purpose limitation says that you must have specified, explicit and legitimate purposes for what you do with personal data, and any further use of the data must be compatible with those purposes. Privacy information that clearly and concisely sets out what you do with personal data will help you meet these requirements. It will also be useful to consult when you are assessing the compatibility of any further uses of that data.

- Consent – When relying on consent as your lawful basis for processing, one of the key elements is that it must be informed. Although requirements for consent requests are separate to the requirements for privacy information, there are clear links between the two. In both cases, providing people with clear and easy to understand information about who you are and what you plan to do with their personal data will help you to be more confident that people are properly informed.

- Legitimate interests – When relying on legitimate interests as your lawful basis for processing, you take on extra responsibility for protecting people’s right and interests. Making sure that people understand and reasonably expect what you do with their personal data is key to relying on this lawful basis. Providing clear, intelligible privacy information will help you do this.

Further reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

The right to be informed is a fundamental aspect of the GDPR and a key obligation for all organisations collecting and using personal data. The ICO prioritises guiding, advising and educating organisations about how to comply with the law, but serious breaches of the right to be informed could leave you open to the highest tier of fines.

Over and above any fines you may be subject to is the reputational damage you could suffer for getting it wrong. If you’re not honest with people about what you do with their data, or you hide important information behind overly complex and legalistic language, people will be less willing to put their trust in you and provide you with their personal data.

-

What privacy information should we provide?

In detail

The GDPR specifies what you need to tell individuals when you collect personal data from them. There are some types of information that you must always provide, while the provision of other types of information depends on the particular circumstances of your organisation, and how and why you use people’s personal data. The table below explains what information you need to provide, what to tell people, and when it is required.

What information do we need to provide? What should we tell people? When is this required? The name and contact details of your organisation Say who you are and how individuals can contact you.

The name and contact details of your representative Say who your representative is and how to contact them. A representative is an organisation that represents you if you are based outside the EU, but you monitor or offer services to people in the EU.

The contact details of your data protection officer Say how to contact your data protection officer (DPO). Certain organisations are required to appoint a DPO. This is a person designated to assist with GDPR compliance.

The purposes of the processing Explain why you use people’s personal data. Be clear about each different purpose. There are many different reasons for using personal data, you will know best the particular reasons why you use data. Typical purposes could include marketing, order processing and staff administration.

The lawful basis for the processing Explain which lawful basis you are relying on in order to collect and use people’s personal data. This is one or more of the bases laid out under Article 6(1) of the GDPR.

The legitimate interests for the processing Explain what the legitimate interests for the processing are. These are the interests pursued by your organisation, or a third party, if you are relying on the lawful basis for processing under Article 6(1)(f) of the GDPR.

The recipients, or categories of recipients of the personal data Say who you share people’s personal data with. This includes anyone that processes the personal data on your behalf, as well all other organisations.

You can tell people the names of the organisations or the categories that they fall within.

Be as specific as possible if you only tell people the categories of organisations.

The details of transfers of the personal data to any third countries or international organisations Tell people if you transfer their personal data to any countries or organisations outside the EU. Say whether the transfer is made on the basis of an adequacy decision by the European Commission under Article 45 of the GDPR.

If the transfer is not made on the basis of an adequacy decision, give people brief information on the safeguards put in place in accordance with Article 46, 47 or 49 of the GDPR. You must also tell people how to get a copy of the safeguards.

The retention periods for the personal data Say how long you will keep the personal data for. If you don’t have a specific retention period then you need to tell people the criteria you use to decide how long you will keep their information.

The rights available to individuals in respect of the processing Tell people which rights they have in relation to your use of their personal data, e.g. access, rectification, erasure, restriction, objection, and data portability. The rights will differ depending on the lawful basis for processing – make sure what you tell people accurately reflects this.

The right to object must be explicitly brought to people’s attention clearly and separately from any other information.

The right to withdraw consent Let people know that they can withdraw their consent for your processing of their personal data at any time. Consent must be as easy to withdraw as it is to give. Tell people how they can do this.

The right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority Tell people that they can complain to a supervisory authority. Each EU Member State has a designated data protection supervisory authority.

Individuals have the right to raise a complaint with the supervisory authority in the Member State where they live, where they work, or where the infringement took place.

It is good practice to provide the name and contact details of the supervisory authority that individuals are most likely to complain to if they have a problem. In practice, if you are based in the UK, or you regularly collect the personal data of people that live in the UK, you should inform people that they can complain to the ICO and provide our contact details.

The details of whether individuals are under a statutory or contractual obligation to provide the personal data Tell people if they are required by law, or under contract, to provide personal data to you, and what will happen if they don’t provide that data. Often, this will only apply to some, and not all, of the information being collected. You should be clear with individuals about the specific types of personal data that are required under a statutory or contractual obligation.

The details of the existence of automated decision-making, including profiling Say whether you make decisions based solely on automated processing, including profiling, that have legal or similarly significant effects on individuals. Give people meaningful information about the logic involved in the process and explain the significance and envisaged consequences. Whilst this type of processing may be complex, you should use simple, understandable terms to explain the rationale behind your decisions and how they might affect individuals. Tell people what information you use, why it is relevant and what the likely impact is going to be.

The information you need to provide is slightly different when you have obtained the personal data from a source other than the individual themselves.

You do not need to tell people about any statutory obligations to provide the personal data, but you do need to give people additional information on the categories of personal data you obtained and the source of that information. The table below details all the information you need to provide, what to tell people, and when it is required.

What information do we need to provide? What should we tell people? When is this required? The name and contact details of your organisation Say who you are and how individuals can contact you.

The name and contact details of your representative Say who your representative is and how to contact them. A representative is an organisation that represents you if you are based outside the EU, but you monitor or offer services to people in the EU.

The contact details of your data protection officer Say how to contact your data protection officer (DPO). Certain organisations are required to appoint a DPO. This is a person designated to assist with GDPR compliance.

The purposes of the processing Explain why you use people’s personal data. Be clear about each different purpose. There are many different reasons for using personal data, you will know best the particular reasons why you use data. Typical purposes could include marketing, order processing and staff administration.

The lawful basis for the processing Explain which lawful basis you are relying on in order to collect and use people’s personal data. This is one or more of the bases laid out under Article 6(1) of the GDPR.

The legitimate interests for the processing Explain what the legitimate interests for the processing are. These are the interests pursued by your organisation, or a third party, if you are relying on the lawful basis for processing under Article 6(1)(f) of the GDPR.

The categories of personal data obtained Tell people what types of information you collect about them.

The recipients, or categories of recipients of the personal data Say who you share people’s personal data with. This includes anyone that processes the personal data on your behalf, as well all other organisations.

You can tell people the names of the organisations or the categories that they fall within.

Be as specific as possible if you only tell people the categories of organisations.

The details of transfers of the personal data to any third countries or international organisations Tell people if you transfer their personal data to any countries or organisations outside the EU. Say whether the transfer is made on the basis of an adequacy decision by the European Commission under Article 45 of the GDPR.

If the transfer is not made on the basis of an adequacy decision, give people brief information on the safeguards put in place in accordance with Article 46, 47 or 49 of the GDPR. You must also tell people how to get a copy of the safeguards.

The retention periods for the personal data Say how long you will keep the personal data for. If you don’t have a specific retention period then you need to tell people the criteria you use to decide how long you will keep their information.

The rights available to individuals in respect of the processing Tell people which rights they have in relation to your use of their personal data, e.g. access, rectification, erasure, restriction, objection, and data portability. The rights will differ depending on the lawful basis for processing – make sure what you tell people accurately reflects this.

The right to object must be explicitly brought to people’s attention clearly and separately from any other information.

The right to withdraw consent Let people know that they can withdraw their consent for your processing of their personal data at any time. Consent must be as easy to withdraw as it is to give. Tell people how they can do this.

The right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority Tell people that they can complain to a supervisory authority. Each EU Member State has a designated data protection supervisory authority.

Individuals have the right to raise a complaint with the supervisory authority in the Member State where they live, where they work, or where the infringement took place.

It is good practice to provide the name and contact details of the supervisory authority that individuals are most likely to complain to if they have a problem. In practice, if you are based in the UK, or you regularly collect the personal data of people that live in the UK, you should inform people that they can complain to the ICO and provide our contact details.

The source of the personal data Tell people where you obtained their information from. If it was from a publicly accessible source you must say this. Be as specific as possible and name the individual source(s) the personal data was obtained from. If you can’t do this because you don’t know the specific source, you should provide more general information.

The details of the existence of automated decision-making, including profiling Say whether you make decisions based solely on automated processing, including profiling, that have legal or similarly significant effects on individuals. Give people meaningful information about the logic involved in the process and explain the significance and envisaged consequences. Whilst this type of processing may be complex, you should use simple, understandable terms to explain the rationale behind your decisions and how they might affect individuals. Tell people what information you use, why it is relevant and what the likely impact is going to be.

-

When should we provide privacy information?

In detail

When you collect personal data from the individual it relates to, Article 13 of the GDPR says that you must provide them with privacy information:

“…at the time when personal data are obtained…”This applies when you collect personal data:

- directly from an individual (eg when they fill-in a form); or

- by observation (eg when you use CCTV or track people online).

ExampleA bank collects personal data from an individual in branch when they fill in a form to apply for a current account. The bank provides information to the individual on the application form to let them know why they need the data and what they do with it. The individual can review this information as they fill in the form.

ExampleThe bank provides its customers with a mobile-banking app so they can manage their current account on the move. The app uses an individual’s location on their smartphone to inform them of nearby offers they can benefit from if they use their debit card. The app provides individuals with information about location tracking at the time of first log-in. App users can choose to accept or decline this use of their personal data.

Further reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

When you obtain personal data from a source other than the individual it relates to, Article 14 of the GDPR says you must provide them with privacy information:

“…within a reasonable period after obtaining the personal data, but at the latest within one month…”This applies when you obtain personal data:

- from another individual or organisation (eg if you buy in personal data, or it is shared with you); or

- from a publicly accessible source (eg the open electoral register).

The GDPR further clarifies that if you plan to use the personal data you obtain to communicate with the individual it relates to, or to disclose to someone else, the latest point at which you must provide the information is when you first communicate with the individual or disclose their data to someone else. Bear in mind that the one month time limit still applies in these situations. If, for instance, you plan on disclosing an individual’s personal data to someone else two months after obtaining it, you must still provide that individual with privacy information within a month of obtaining the data.

Whatever the situation, you must consider the specific circumstances of your use of the personal data in deciding when it would be reasonable to provide privacy information to an individual. You are accountable for demonstrating that what you did was fair. In practice this means that you need to think carefully about the reasonable expectations of individuals and what effects your use of their data may have on them.

The need to provide people with privacy information as soon as possible after obtaining their personal data is strongest where:

- your use of the data is likely to be unexpected or unwelcome;

- your use of the data is likely to have a significant effect on individuals; or

- you have obtained special categories of personal data or criminal conviction and offence data.

ExampleA council obtains the names and contact details of the members of several voluntary groups in its area, from each group’s secretary. It intends to send letters to the members to invite them to a training event it is running on child safeguarding. The council assesses that the voluntary group members are unlikely to be significantly affected by, or object to, this use of their data. As such, it provides the members with the appropriate privacy information at the point at which it first communicates with them about the training event, two weeks after obtaining their data.

ExampleThe council also obtains the names and contact details of members of other voluntary groups in its area. It intends to disclose their details to a market research company that is conducting a survey on the council’s behalf to gauge public opinion on council services. The council assesses that the voluntary group members are less likely to expect their data to be used in this way and may object to being contacted by the market research company. As such, it decides to provide the voluntary group members with information about its intention to pass their details on to the market research company as soon as it obtains their personal data, and well in advance of any disclosures actually taking place. The council also uses this opportunity to seek the consent of the voluntary group members to use their data for the new purpose.

Prior to obtaining personal data, it is good practice to use a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) to identify the risks of what you plan to do, and then build in appropriate measures and safeguards, including deciding when to provide individuals with privacy information and what your lawful basis is for a further use of personal data. The use of a DPIA is a legal requirement when what you plan to do with personal data is likely to result in a high risk to individuals’ rights and freedoms, particularly when new technologies are involved.

Further reading - ICO guidanceFurther reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

The GDPR says that you must “provide” individuals with the necessary information in an “easily accessible form”. This applies equally if you collect personal data from the individual it relates to or if you obtain personal data from another source.

You can meet this requirement by putting the information on your website (this is often how organisations deliver privacy information), however you must proactively make individuals aware of this information and you need to give them an easy way to access it. Simply putting it on your website, in case people happen to look there, is not enough.

In practice, the way in which you provide privacy information to individuals will depend on the circumstances of how you collect or obtain their personal data. Some of the different techniques you can use to deliver this information are covered later in this guidance in the section ‘What methods can we use to provide privacy information?’

-

Are there any exceptions?

In detail

There are a small number of built in exceptions from the right to be informed in the GDPR. The Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018) also provides some other exemptions from this obligation. These are detailed below.

There is no automatic exception from the right to be informed just because the personal data is in the public domain. You should still provide privacy information to individuals, unless you can rely on a specific exception or exemption. Please see ‘What common issues might come up in practice?’ for more details.

The exceptions available in the GDPR depend on how you have obtained an individual’s personal data.

When you collect personal data directly from the individual it relates to, you do not need to provide them with privacy information if:

- The individual already has the information – If you know, or it’s obvious, that an individual already has some of the necessary information, you do not need to provide it to them. However, you must still provide them with anything that they don’t already have. In practice, you may not know what information an individual already has. If you are unsure, it is best to provide individuals with all the relevant privacy information.

When you obtain personal data from a source other than the individual it relates to, you do not need to provide them with privacy information if:

- The individual already has the information – You must be able to demonstrate that the individual already has the information. You may need to conduct due diligence checks on the source from which you obtained the personal data to verify what information the individual has been provided with. If you are unsure what information an individual already has, you should provide them with all the relevant privacy information. Further guidance on what to do when personal data is sold or bought is provided in the section ‘What common issues might come up in practice?’

- Providing the information to the individual would be impossible – You need to be able to show that it is impossible, not just inconvenient. See ‘When can we rely on impossibility?’ below for more details.

- Providing the information to the individual would involve a disproportionate effort – You must be able to show that the effort involved in providing the information is not warranted by the impact on individuals. See ‘When can we rely on disproportionate effort?’ below for more details.

- Providing the information to the individual would render impossible or seriously impair the achievement of the objectives of the processing – You must justify why providing an individual with privacy information would make it impossible, or impair your ability, to achieve what you want to by using that particular individual’s personal data. This is most likely to occur in an investigatory context.

ExampleA local authority obtains information about an individual’s working hours and pay from their employer for the purposes of a benefit fraud investigation. The local authority decides that telling the individual about the collection of their personal data would seriously impair the progress of the investigation because the individual might destroy further evidence necessary to prove an offence. As such, the local authority documents its justification for this decision and does not provide the individual with any privacy information in this instance.

- You are required by law to obtain or disclose the personal data – You need to satisfy yourself that the law in question actually imposes a requirement on you (or your organisation) to obtain or disclose an individual’s personal data. Remember that this exception can only apply to personal data you obtain from a source other than the individual it relates to, and not to personal data you collect from the individual themselves.

- You are subject to an obligation of professional secrecy regulated by law that covers the personal data – In practice, this exception is most likely to apply to personal data processed by professionals in sectors such as tax, health, social work, law and HR.

ExampleAn individual provides information to their social worker in confidence about a family member. If providing privacy information to that family member would result in a breach of confidence, the social worker is exempt from the requirement to provide the information.

Further reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

Situations in which it is impossible to provide privacy information to individuals are few and far between. This is most likely to occur if you do not have any contact details for individuals and have no reasonable means to obtain them.

If you determine that providing privacy information to individuals is impossible, you must publish the privacy information (eg on your website), and you should carry out a DPIA. See ‘What else should we consider if we want to rely on an exception?'.

ExampleA public library is engaged in a project to collect, organise and archive information on defunct clubs and societies that operated in the local area over the past 100 years. Amongst other things, the records in question contain membership details including people’s titles and names, but not any address or contact information. It is impossible for the library to provide the individuals with any information about what it is doing because it does not have any contact details. As such, it publishes the relevant privacy information on its website. The library also carries out a DPIA and as a result it decides to publicise the project in a local newspaper in order to direct people to the privacy information on its website.

To rely on this exception, you must make (and document) an assessment of whether there is a proportionate balance between the effort involved for you to provide individuals with privacy information and the effect that your use of their personal data will have on them. The more significant the effect, the less likely you will be able to rely on this exception.

This is an exception to the general obligation of transparency, and should be treated as the exception, not the rule. You should not use it to routinely escape your obligations to inform individuals about your use of their data. If you want to rely on disproportionate effort, you need to be confident you can justify why contacting individuals is genuinely disproportionate in the particular circumstances.

The GDPR says (particularly if you use personal data for archiving or research purposes) you should take into account:

- the number of individuals involved;

- the age of the personal data; and

- any appropriate safeguards you have adopted.

If you determine that providing privacy information to individuals does involve a disproportionate effort, you must still publish the privacy information (eg on your website), and you should carry out a DPIA. See ‘What else should we consider if we want to rely on an exception?'

ExampleAt the start of each academic year, a school obtains the name and contact details of individuals when it collects emergency contact information from the parents or guardians of children that have enrolled that year. The school assesses that the effort involved for it to write to every emergency contact to provide them with privacy information is disproportionate in relation to the effect that the use of their personal data will have on them (contacting them in the event of an emergency). As such, the school does not actively provide privacy information to each emergency contact, however it does publish information on the use of emergency contact details on its website. It also carries out a DPIA and decides that to further mitigate any risks, it will put a policy in place to specify the strict limited use of emergency contact details, and places restrictions on its computer system so that only authorised members of staff have access to these details.

You need to consider the effect on the overall lawfulness, fairness and transparency of your processing, and whether you need to put in place additional safeguards.

Even if you are justified in relying on an exception, if you don’t actively provide an individual with privacy information this can cause ‘invisible processing’. The processing is ‘invisible’ because the individual won’t be aware that you are collecting and using their personal data.

Invisible processing results in a risk to the individual’s interests as they cannot exercise any control over your use of their data. In particular, they are unable to use their data protection rights if they are unaware of the processing. This is true even if the processing itself is unlikely to have any negative effect.

Given these risks, if you intend to rely on the exceptions for impossibility or disproportionate effort, you must still publish your privacy information, and you should carry out a DPIA. A DPIA will help you to assess and demonstrate whether you are taking a proportionate approach. It will help you consider how best to mitigate the impact on individuals’ ability to exercise their rights. It will also help you demonstrate how you comply with fairness and transparency requirements. For more details, read our guidance on data protection impact assessments.

You should also consider the impact on your lawful basis for processing. In particular, you may find it difficult to rely on legitimate interests if you process personal data in ways the individual does not reasonably expect and you do not provide privacy information. The GDPR is clear that the interests of the individual are more likely to override your interests in these circumstances. You would need to be confident that you have a compelling reason to justify the unexpected nature of the processing, and can mitigate the impact on individual rights. For more information, see our separate detailed guidance on legitimate interests and the impact of reasonable expectations.

In more detail – ICO guidanceThe DPA 2018 provides several other potential exemptions from the right to be informed.

Depending on what you do with personal data, a number of these exemptions may be familiar to you, covering areas such as national security, crime and taxation, and legal proceedings. Others may be less familiar such as the exemption relating to the use of personal data for immigration control.

Please see our separate guidance on the exemptions for more details.

-

How should we draft our privacy information?

In detail

Before you start drafting your privacy information, you need to know what personal data you have and what you do with it. To help you with this you may need to do an information audit or data mapping exercise. You should map out how information flows through your organisation and how you process it, recognising that you might be doing several different types of processing.

You may already undertake this type of audit or mapping exercise as part of your existing data governance framework, or as part of documenting your processing activities under Article 30 of the GDPR. If this is the case, you can incorporate the privacy information requirements into this process.

You should work out:

- what information you hold that constitutes personal data;

- what you do with the personal data you process;

- why you process the personal data;

- where the personal data came from;

- who you share the personal data with; and

- how long you keep the personal data for.

Once you have an understanding of the above, you can build on this by addressing some of the more specific questions that you need to be able to answer, such as:

- Which lawful basis do you rely on for each type of processing?

- What are the legitimate interests for processing (if applicable)?

- What rights do individuals have in relation to each type of processing?

- Is there a legal or contractual obligation for individuals to provide personal data to you?

- Do you make solely-automated decisions about people that have legal or similarly significant effects?

You also need to think about your audience, as this will help you keep your information clear and easy to understand.

Further reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on automated individual decision-making and profiling, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

You also need to think about who you are addressing your privacy information to. It is a good idea to put yourself in the position of the people you’re collecting information about. You need to understand the level of knowledge your intended audience has about how their data is collected and what is done with it.

- Dealing with a wide range of individuals - If you collect the personal data of a wide range of individuals you need to think about the relationships you have with the various groups and whether they will all understand the information you give them. Break your customers down into different categories and provide tailored privacy information for each group.

ExampleAn insurance company provides business travel insurance to large multi-national organisations and travel insurance to members of the public. It tailors the privacy information it provides to these different customers to cater for the differing levels of understanding and uses of personal data.

- Dealing with vulnerable individuals, including children – The GDPR emphasises that the requirement to provide information using clear and plain language is of particular importance when addressing a child. While children are singled out as meriting special protection, in practice if you collect information from any type of vulnerable individual, you must make sure you treat them fairly.

This means drafting privacy information appropriate to the level of understanding of your intended audience and, in some cases, putting stronger safeguards in place. You should not exploit any lack of understanding or experience, for example, by asking children to provide personal details of their friends.

There may be times when using a combination of the techniques described in this guide may not be effective, as it could cause confusion or provide less clarity. If this is likely to be the case, the key point is to focus on providing clear and understandable information for the target audience.

You should use your knowledge of the individuals you deal with to decide your approach. In particular, you should try to work out whether the individuals you are collecting information about would understand the consequences of this. If in doubt, you should be cautious and should instead ask the individual’s parent, guardian or carer to provide the information. For online services, if you rely on consent for the collection of personal data, the GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018 require that you obtain it from the holder of parental responsibility for children under the age of 13.

- Dealing with people whose first language is not English - Sometimes you may want to collect personal data from people whose first language is not English. In some cases you may be obliged by law (other than data protection) to provide information in another language, for example, Welsh. Even where this is not the case, it is good practice to provide your privacy information in the language that your intended audience is most likely to understand.

Further reading - ICO guidanceOne of the biggest challenges is to encourage people to read privacy information. People are often unwilling to engage with detailed explanations, particularly where they are embedded in lengthy terms and conditions. This does not mean that providing privacy information is a mere formality; it means that you have to write and present it effectively. The GDPR recognises this and requires that the information you provide individuals with meets the following standards.

- Conciseness – There is a tension between the amount of information you need to provide individuals with and the requirement that it must be concise, but there are ways of writing and presenting privacy information that can achieve both:

- Use an appropriate technique to deliver the information, such as a layered approach (see 'What methods can we to provide privacy information?').

- Use headings to separate the information into easily digestible chunks, each dealing with a different aspect of what you do with personal data.

- Keep your sentences and paragraphs short. Omit any irrelevant or unnecessary information.

- Transparency – Being transparent is about being open, honest and truthful with people:

- Don’t offer individuals choices that are counter-intuitive or misleading.

- Don’t hide information from people; make sure that you clearly bring to people’s attention any uses of data that may be unexpected, or could have significant effects on them.

- Align your privacy information with your organisation’s values and principles. People will be more inclined to read it, understand it, and trust your handling of their personal data.

- Intelligibility – Your privacy information needs to be understood by the people whose personal data you collect and obtain:

- Adopt a simple style that your audience will find easy to understand.

- Don’t assume that everyone reading the information has the same level of understanding as you. Explain complex matters in basic terms.

- Ensure that what you say is unambiguous. Be as precise as you can about what you do with people’s data.

- Ease of access – Individuals should not have to look for your privacy information, it must be easy for them to access:

- Adapt how you provide your privacy information to the context in which you collect or obtain people’s data.

- If you provide individuals with a link, ensure that you direct them straight to the relevant privacy information and do not have to seek it out amongst other information.

- Make the information consistently easy to access across multiple platforms.

- Clear and plain language – Ensure that the words and phrases you use are straightforward and familiar for your intended audience:

- Use common, everyday language.

- Avoid confusing terminology, jargon, or legalistic language.

- Align to your house style. Use expertise (for example in-house copywriters) to help your privacy information fit with the style and approach your customers expect.

Further reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

Carrying out user testing will provide useful feedback on draft privacy information. This is where you select a sample of your customers and ask them to access and read the information to obtain their feedback on:

- how they accessed it;

- if they found it easy to understand;

- whether anything was difficult, unclear or they did not like it; or

- if they identified any errors.

Asking your customers to do this will help you improve the effectiveness of your delivery of the information. You are likely to come up with a far more useful and engaging approach if you consider feedback from the people it is aimed at.

ExampleYou plan to deliver privacy information to people based on assumptions you made about a user’s journey around your website. However, during your user testing you identify that people are often directed to a specific page of your website straight from a third party search engine and therefore miss some of the information supplied on your homepage. Having identified this, you ensure that your privacy information is correctly connected together so that individuals do not miss anything important. For instance, you provide a link to more detailed information in all your just-in-time notices so that an individual can see the important message at that point in the journey but can also refer to further information to see if they have missed anything.

Having made any changes to the content and delivery of your privacy information as a result of user testing, you are then ready to roll it out using the tools and approaches you have selected.

Further reading – European Data Protection BoardThe European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

You need to regularly review the information to:

- check that it actually explains what you do with individuals’ personal data;

- ensure that it remains accurate and up to date; and

- analyse complaints from the public about how you use their personal data and in particular any complaints about how you explain your use of it.

If you plan to use personal data for a new purpose, you need to tell people about this before you do so. In these circumstances, you must update your privacy information to reflect what you intend to do with people’s data, and proactively bring this change to their attention before you start any new processing. In particular, you must provide people with information on the new purpose for processing, along with any relevant further information concerning:

- your retention period for the personal data that you are processing for the new purpose;

- the rights available to individuals in respect of the new processing;

- the right to withdraw consent for the processing;

- the right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority;

- the source of the personal data (if you obtained it from a source other than the individual);

- the details of whether individuals were under a statutory or contractual obligation to provide the personal data (if you collected it from the individual); and

- the details of the existence of automated decision-making, including profiling (if it is solely automated and has legal or similarly significant effects).

If you do not obtain consent for the new processing, as well as updating your privacy information, you must also take into account the purpose limitation principle. This means making an assessment of whether what you plan to do is compatible with the original reason you collected or obtained the personal data.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

- Guidelines on Transparency

- Guidelines on Consent

- Guidelines on the right to data portability

- Guidelines on automated individual decision-making and profiling

Further reading

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) commissioned research and a guide on how to best present information to individuals. Whilst this relates to terms and conditions generally, it contains recommendations for presenting privacy information which may be useful.

-

What methods can we use to provide privacy information?

In detail

Yes, you should not necessarily restrict the delivery of privacy information to a single notice or page on your website. The term ‘privacy notice’ is often used as a shorthand term, but rather than seeing the right to be informed as being about delivering a single notice, it is better to think of it as providing privacy information in a range of ways. You can provide this information through a variety of media:

- Orally - face to face or when you speak to someone on the telephone (it’s a good idea to document this).

- In writing - printed media; printed adverts; forms, such as financial applications or job application forms.

- Through signage - for example an information poster in a public area.

- Electronically - in text messages; on websites; in emails; in mobile apps.

It is good practice to use the same medium you use to collect personal data to deliver privacy information. So, if you are collecting information through an online form you could provide a just-in-time notice as an individual fills in the form. You can combine this with more detailed information on your website, accessible through a clear and prominent link on the online form.

Example

A retailer collects personal data on an online form. It provides individuals with a message at the point they enter their email address explaining that they will use it for order processing (the purposes of the processing). The message has a prominent link to more detailed information telling individuals that they will share the email address with an external courier company (the recipient) and they will keep it for two years (the retention period).

A blended approach, such as this, is often the most effective way to provide privacy information. Where appropriate, you should incorporate a variety of techniques, taking advantage of all of the technologies available to you. Examples of techniques you can use include:

- a layered approach;

- dashboards;

- just-in-time notices;

- icons; and

- mobile and smart device functionalities.

It is often beneficial (and sometimes necessary) to consider these solutions as part of a DPIA. Always remember to focus on the individual when you make decisions about the way to deliver privacy information.

Relevant provisions in the GDPR - See Articles 13(1)-(2), 14(1)-(2) and 35, and Recitals 84 and 90-91External link

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIA)

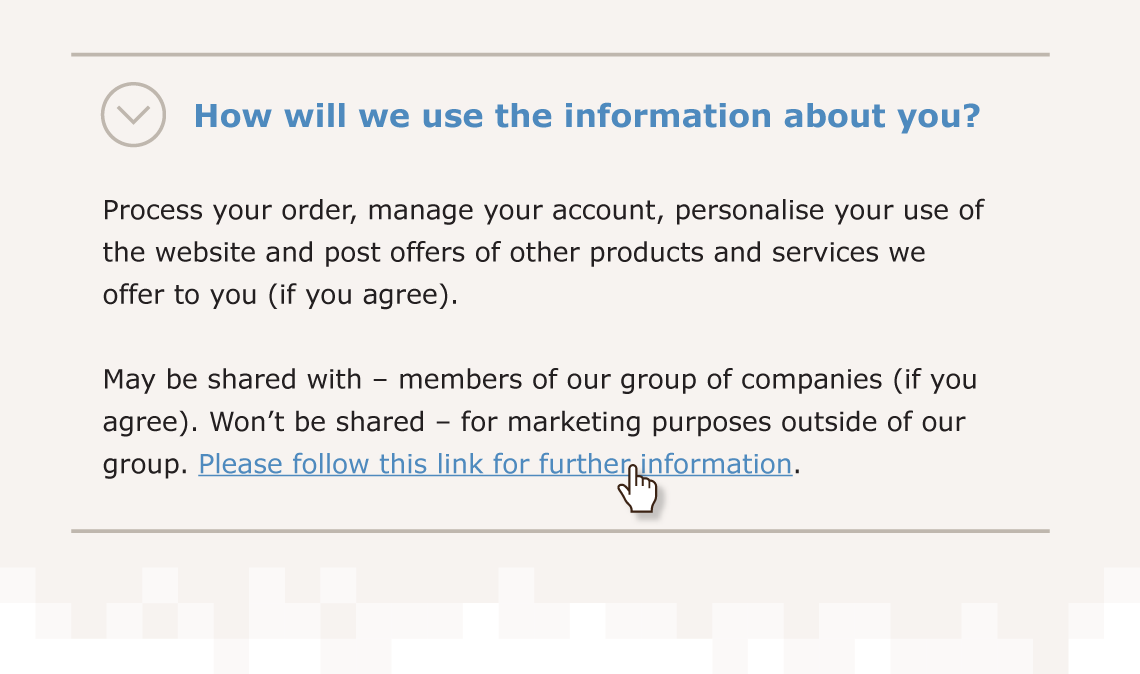

A layered approach to delivering privacy information typically consists of providing people with a short notice containing key information, such as the identity of your organisation and the way you use the personal data. It may contain links that expand each section, revealing a second layer, or a single link to more detailed information. These can, in turn, contain links to further material that explains specific issues, such as the circumstances in which personal data may be disclosed to the police.

A layered approach is useful as it allows you to provide key privacy information immediately and have more detailed information available elsewhere for those that want it. This is particularly valuable when there is limited space to provide more detail, or if you need to explain a complicated information system to people.

There will always be pieces of information that are likely to need to go into the top layer, such as who you are, what information you are collecting and why you need it. What else goes into which layer will depend on the type of processing that you undertake. The ICO considers that data controllers have a degree of discretion as to what information they consider needs to go within each layer, based on the data controller’s own knowledge of their processing.

Regardless of how you choose to layer your privacy information, you must treat people fairly. This means considering what people might (or might not) reasonably expect you to do with their personal data, and how your processing may affect them. Therefore, the top layer should always give people prominent, early warning of any use of their information that is likely to be unexpected, objectionable, or significantly affect them.

If you are unsure whether what you plan to do with personal data would be reasonably expected or have significant effects, there are a number of things you can do to get a more informed picture about your customers:

- Consult with your customers as part of a data protection impact assessment.

- Undertake more general research with the wider public, explaining what you would like to do and from that gauge whether or not they would reasonably expect you to do what you’re planning. You could use focus groups or online questionnaires.

- If you are planning on doing something similar to what you have done in the past, review whether you had any issues when implementing new processing or if you received a lot of complaints about it.

- Look at the experience of others in your sector or industry to see if there has been an approach that has been welcomed by customers or worked particularly well.

Using a layered approach works very well in an online context, where it is easy to provide a prominent front page link. It is also useful if you have further sectoral requirements that mean you need to present other information in addition to the privacy information. For example, information regarding fraud in the financial sector. As this increases the amount of information you have to provide, it is even more important that you present it in a clear and engaging manner.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIA)

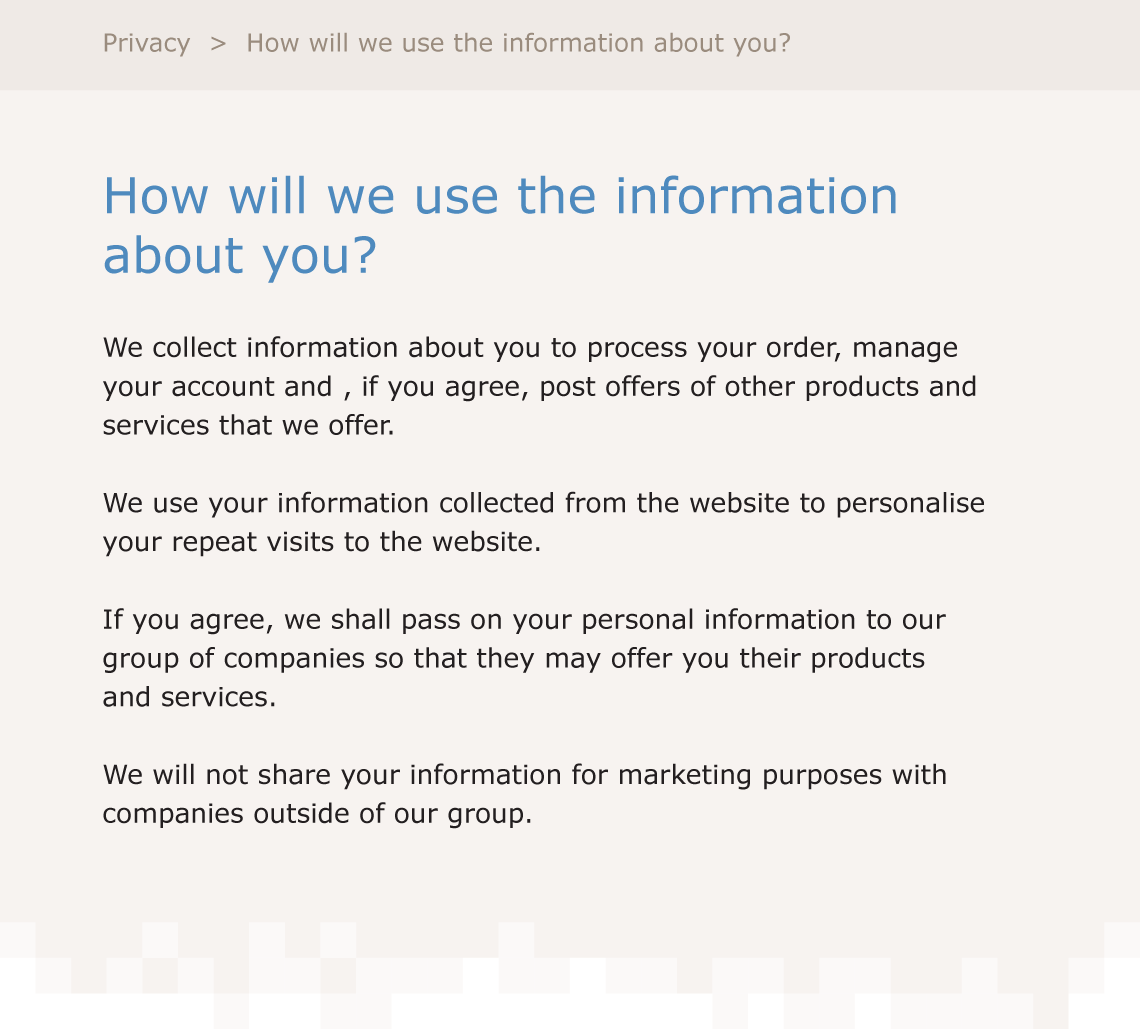

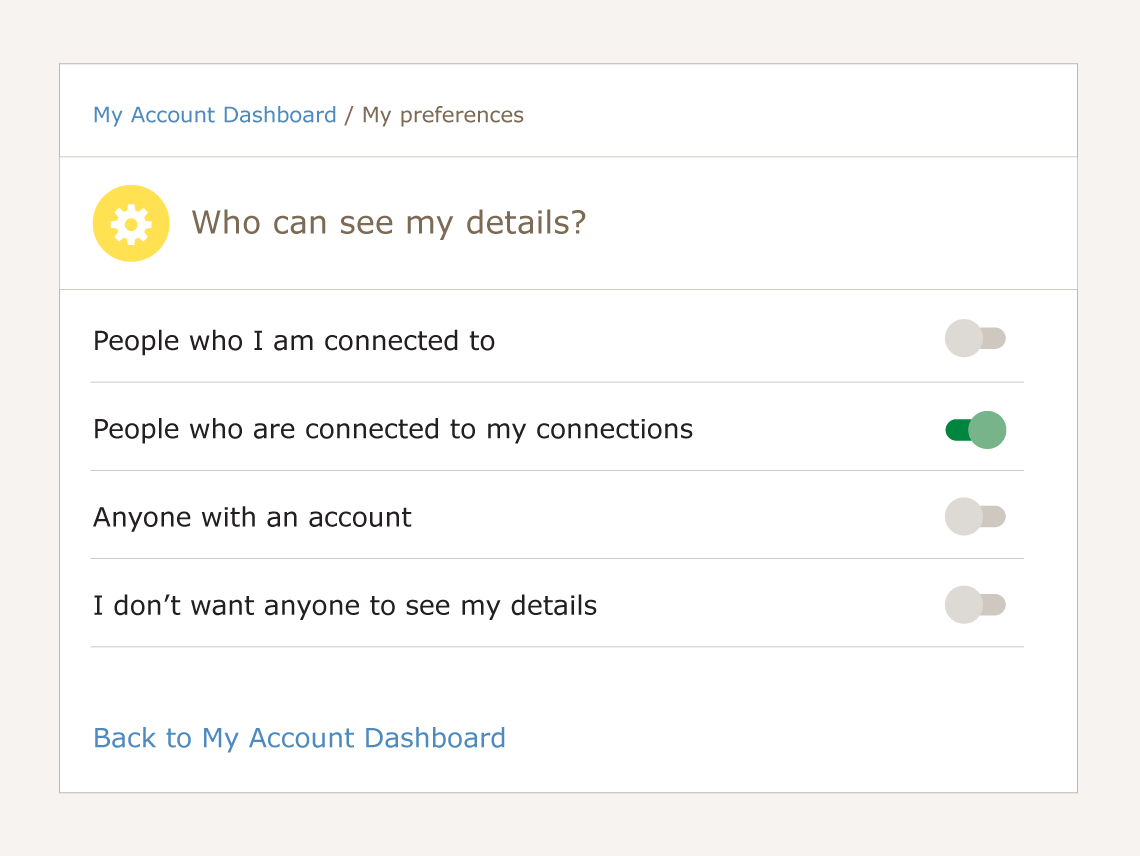

A dashboard is a preference management tool that can give people a place from which to manage what is happening to their personal data. For individuals it allows them to alter settings, so that (where consent is relevant) they are able to clearly indicate that they agree to the particular processing or data sharing. It also allows for individuals to provide consent and revoke it over time, as processing develops or if they change their minds. This can help you to meet the GDPR’s requirement that consent must be as easy to withdraw as it is to provide.

It is good practice to link to your dashboard from the places where you give people privacy information. This allows individuals to manage their preferences and to prevent their data being shared where they have a choice. You can also embed, or link to, your privacy information from within the dashboard itself. If you process personal data across a number of applications or services, this will help people to stay informed, and maintain control over, what is happening with their personal data, all in one place. See below for an example of how this can be done in practice.

Building individuals’ awareness and confidence in tools like dashboards is likely to make them more informed and better placed to engage with messages about what is happening to their information and how to manage it. Ultimately this should help to build trust and confidence with your customer.

A well designed and easily accessible dashboard is also an excellent way to allow individuals to exercise their rights, something that the GDPR requires you to do. For instance, you can use your dashboard to allow people to object to a particular use of their information, or access a copy of their personal data in a re-usable and machine readable format.

Further reading - European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

Guidelines on the right to data portability

Guidelines on automated individual decision-making and profiling

A just-in-time notice appears at the point where an individual provides you with a particular piece of information. The notice gives the individual a brief message explaining how you will use the information they are about to provide.

Just-in-time notices are particularly useful when people provide personal data at different points of a purchase or interaction, often on an organisation’s website, when filling in a form. People may not think about the impact that providing the information will have at a later date. Just-in-time notices help to resolve this issue by providing relevant and focused privacy information in such situations.

These notices can be most effective when used in combination with other techniques, ensuring that individuals who want more information are easily able to access it.

The individual can either choose to carry on with the basic information or click on the link to find out more information. This can expand the box or direct them to another page to explain in detail what you will do with the personal information they have provided.

You can achieve a similar result using the hover over feature when completing fields in an online form.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

While it is not a legal requirement, the GDPR says that you can provide privacy information to individuals:

“…in combination with standardised icons in order to give in an easily visible, intelligible and clearly legible manner a meaningful overview of the intended processing.”The European Commission (the EC) is empowered to set out how to provide standardised icons, and what they should represent. Although the EC is yet to do this, you can still use icons effectively in the meantime. Icons can be very useful, for instance, for indicating to individuals that a particular type of data processing is occurring.

Example

An icon indicating that information will be used for marketing appears when an individual inputs their email address into an online form. Hovering over the icon reveals the word ‘marketing’, and clicking on it directs the individual to a more detailed explanation of what will be done with their email address.

You can also use icons as useful reminders that data processing is taking place, especially if that processing is intermittent. This approach is often used on smartphones to indicate whether or not a particular app is processing location data, by placing a recognisable icon in the status bar.

The design of any icon is important as you need to make the messages they convey as clear as possible. Use icons consistently and make sufficient information available so that people understand what they mean; you should produce a key to the icons that can be accessed easily by users.

It is also important to limit the number of icons you use, as people are unlikely to take the time to learn what a large number of different icons mean. If you are a large organisation, it might make sense to have a single set of icons that you can use across all of your operations. The icons can be designed with your brand in mind so that they fit with the look of your websites.

Bear in mind that if your icons are presented electronically, the GDPR says you must make them available in a machine readable form. This means that electronic devices can ‘read’ the information the icon conveys.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

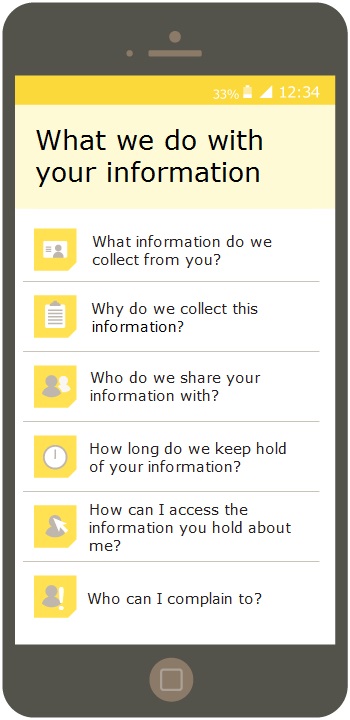

Mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets have limitations in relation to the delivery of privacy information. The primary issue is the size of the screen.

You must ensure that any information delivered on mobile devices is as clear and readable on a smaller screen as it would be on a more traditional computer or laptop screen. The text should be large enough to read and people should not have to zoom in to see it. Information should fit on the screen as normal.

A useful tool for this is responsive web design. This allows you to create a website that can change the information on the screen to the optimal setting for viewing that information, depending on the type of device it is viewed on.

The limited screen space on mobile devices also underlines the importance of using a combination of techniques to deliver privacy information. Icons and layering for instance lend themselves well to smaller screens, ensuring that information is presented concisely.

The use of video to convey privacy information is also particularly suitable for smaller devices as lack of space for text is not an issue. Although you are unlikely to be able to convey all the necessary detail in a video, you can direct individuals to more detailed information as appropriate. Keeping the video short and to the point will also avoid any issues individuals may have with data usage if Wi-Fi isn’t available.

View an example video on the Vyond website (external link).

As well as considering the limitations of mobile devices, you should also look to exploit the unique functionalities that they offer when delivering privacy information. You can use:

- pop-ups to deliver just-in-time notices;

- voice, sound and vibration (or haptic feedback) alerts to indicate certain uses of data (eg wifi or location tracking);

- pressure sensitive displays to allow individuals to access additional layers of privacy information without leaving the page they’re on; and

- common mobile device gestures, such as swiping, to reveal more detailed information or to control different uses of data (eg swipe right to consent to marketing).

Always remember to put the individual at the heart of what you’re doing. Try not to adopt approaches that people won’t find intuitive or that result in giving individuals constant alerts regarding their information. This is where a link to a dashboard or preference management tool may be helpful, so people can choose their own settings.

Other types of smart device present their own problems for the delivery of privacy information. Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as home assistants, connected toys and smart metres often don’t have screens on which to provide individuals with written information.

As with mobile devices, you should use a combination of techniques and adapt your approach to cater for the unique limitations and opportunities that IoT devices present:

- Use the audio functionality of IoT devices to provide key privacy information through device speakers, complemented by more detailed information available in a written notice.

- Inform individuals when a smart device is observing or recording them using a red light or a sound alert.

- Use icons on the device, or packaging, to inform individuals how their personal data will be used.

- Link, or send, more detailed privacy information to a device with a screen, using wirelessly technology such as Bluetooth, QR codes, SnapTags or NFC.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

Further reading

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) commissioned research and a guide on how to best present information to individuals. Whilst this relates to terms and conditions generally, it contains recommendations for presenting privacy information which may be useful.

-

What common issues might come up in practice?

In detail

If you set out to collect personal data with the intention of selling it to (or sharing it with) third parties, you must inform people as part of the privacy information you provide. You must tell them who you will give their information to and why, unless you are relying on an exception or an exemption (see 'Are there any exceptions?'). You can tell people the names of the organisations or the categories that they fall within in. You should choose the option that is most meaningful and useful for individuals, bearing in mind what you are doing with their personal data.

Example

An online retailer uses several different companies to handle financial transactions with its customers via a number of payment methods. The retailer decides that providing its customers with the specific names of all these companies is not meaningful for its customers as it is not clear who the companies are or what they do. As such, it tells its customers that their payment details are passed to payment processing companies when an order is placed.

The same retailer also sells the names, contact details and purchase histories of its customers to other retail companies for the purposes of postal marketing. The retailer provides its customers with the specific names of the organisations that it sells their information to, as opposed to the categories they are in. It does this so that its customers are informed about exactly who holds their personal data and can easily exercise their rights about its use.

If you determine that it is most meaningful to provide individuals with the names of the organisations that you pass their information to, this does not necessarily mean that you need to list every organisation up front. If there are a large number of organisations it is a good idea to take a layered approach (see 'What methods can we use to provide privacy information?') to providing this information. For instance, in an online context, you can give individuals a link to the full list of the organisations.

It is also good practice to embed links to tools like dashboards (see 'What methods can we use to provide privacy information?') in the places that you provide people with privacy information. This allows individuals to manage their preferences and to prevent their data being sold or shared where they have a choice. Selling or sharing personal data is one area in which using an icon (see 'What methods can we use to provide privacy information?') alongside your privacy information may also be helpful.

In terms of timing, when you collect information from the individual it relates to, you must tell them who you will give their information to at the point you obtain it. If you obtain personal data from a source other than the individual it relates to, you need to tell the individuals who their information will be passed to no later than one month after obtaining the information. If, however, the personal data is given to another organisation within a month of obtaining it, you must tell the individuals about this, at the latest, when the information is passed on.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 adopted guidelines on Transparency, which have been endorsed by the EDPB.

When buying personal data from another organisation, you must provide people with your own privacy information, unless you are relying on an exception or an exemption (see 'Are there any exceptions?'). If you rely on the exception that providing the privacy information would be impossible, or that it would involve a disproportionate effort, you must carry out a DPIA in order to identify and mitigate the risks associated with your use of the personal data.

It can be useful to check the information that the other organisation provided people with to see what they have, and haven’t, been informed about. If you are unsure as to whether people have been provided with the relevant privacy information, you should make sure to provide this to them yourself. Remember that, because you are not obtaining personal data from the individual it relates to, you need to tell them about the different types of information you collected about them, as well as the source of that information.

If what you plan to do with people’s personal data is different to what they were originally told you must make sure that the privacy information you provide them with reflects the new purpose for using the data. As well as doing this, you will also need to consider (and tell people) what your lawful basis is. You may need to assess whether the new use is compatible with the original purpose for which the personal data was obtained.

You need to provide people with your privacy information within a reasonable period of buying their personal data, and no later than a month. To ensure that what you are doing is fair, as well as transparent, you should do this sooner rather than later, especially if individuals would not reasonably expect what you plan to do with their personal data or if it would have a significant effect on them.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIA)

The fact that personal data is publicly available does not mean that individuals no longer have the right to be informed about any further uses of their information. If you obtain personal data from publicly accessible sources (such as social media, the open electoral register and Companies House), you still need to provide individuals with privacy information, unless you are relying on an exception or an exemption (see 'Are there any exceptions?'). As above, if you rely on the exception that providing the privacy information would be impossible, or that it would involve a disproportionate effort, you must carry out a DPIA in order to identify and mitigate the risks associated with your further use of personal data.

Organisations sometimes obtain information from publicly accessible sources in order to combine, match or add to information that they already hold on an individual (or that they have bought in). This can be particularly intrusive, and unexpected, as it can create a very detailed picture of an individual’s affairs. If you intend to do this, you need to tell people about it. This is a clear example of where it is appropriate to highlight this information to people, for instance by including it in the first layer of a layered privacy notice. This type of processing also requires you to carry out a DPIA, due to the high risks involved.

Whatever you plan to do with personal data obtained from publicly accessible sources, you need to ensure that you have a valid lawful basis and you must tell people what this is in the privacy information that you provide to them. The lawful basis you rely on will affect the rights that individuals have in relation to your use of their personal data. Your privacy information must make clear what rights people have, and in particular, the right to object must explicitly brought to people’s attention.

You need to provide people with your privacy information within a reasonable period of obtaining it. The latest point at which you can do this is one month after the personal data is obtained, but depending on the circumstances, it will not always be fair to wait this long. People’s reasonable expectations about how their personal data may be further used will differ depending on the nature of the personal data and the type of publicly accessible source from which you obtained it. Where further uses of publicly available personal data are less likely to be expected, or could significantly affect individuals, you should provide them with your privacy information as soon as possible after it is obtained.

Further reading – European Data Protection Board

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which has replaced the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), includes representatives from the data protection authorities of each EU member state. It adopts guidelines for complying with the requirements of the GDPR.

WP29 published the following guidelines which have been endorsed by the EDPB:

Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIA)

Guidelines on the right to data portability

The use of AI raises particular issues about data protection and transparency, where personal data is used. AI can typically involve processing large volumes of information and using algorithms to detect trends and correlations, often for the purposes of automated decision making and profiling. In some cases this type of processing can have a relatively limited impact on individuals but in others it can be extremely intrusive and have significant effects.

People often have limited awareness that information about them is being gathered and processed in this way. Although it can be more difficult to foresee at the outset how you will use personal data in this context, you still need to give people an indication of what you are doing with their data. If necessary, you should add additional detail to your privacy information as you go on, making sure to bring this to people’s attention. It can be useful to use just-in-time notices to deliver this type of information to people.

If you use AI to make decisions about people or to profile them, you need to be upfront about it and explain your purposes for doing so. If the decisions are solely automated and have legal or similarly significant effects, you must provide people with extra detail on the logic involved, the significance of the processing and the envisaged consequences of it. In practice, this means telling people what information you use, why it is relevant and what the likely impact is going to be. The way you provide this information to people must be clear and meaningful, you should not confuse people with overly complex explanations of the analytics.

Applying AI to personal data can often find new uses for it. If you obtained information for one purpose but you now intend to use it for another you must tell people about this before you start any new processing. This means updating your privacy information and proactively bringing the changes to people’s attention. You can use a dashboard (see 'What methods can we use to provide privacy information?') to alert people to changes in the use of their data and to allow them to exercise their rights in relation to the new processing.

As well as new purposes, AI can also create new data about people. For instance, you might use a machine learning algorithm to profile people so that you can infer or predict their interests. If you know what type of new personal data you plan to create you should tell people this in advance as part of your explanation of the purposes for processing. However, AI can also reveal unexpected patterns in data. If you create new information about people that they would not reasonably expect you to have, and you plan to keep and use this data, you need to tell them about this within a reasonable period of its creation, and within a month at the latest.

Using AI can deliver a wide range of benefits, but it is often opaque to the individuals whose data is being processed, and may produce unexpected consequences for them. If you are using data in this way it is important to build a relationship of trust with people. Being open about what you do, and finding effective ways to deliver privacy information are both key to that relationship.

Further reading – ICO guidance

Big data, artificial intelligence, machine learning and data protection

Further reading – European Data Protection Board